Norman Foster : « My quest is for a holistic approach that achieves a balance with nature. »

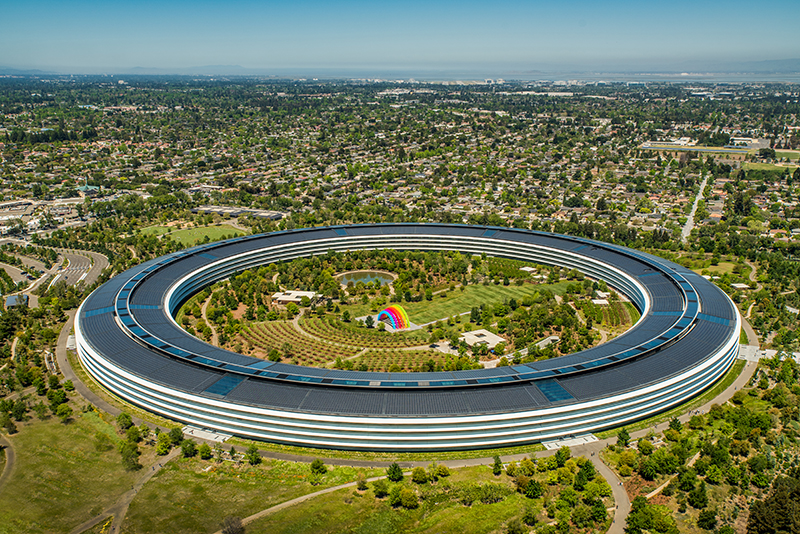

A major figure in global architecture and often considered a leader of the "high tech" movement, British architect Norman Foster has created numerous iconic buildings around the world, such as the HSBC headquarters in Hong Kong (1979-1986), the Carré d'Art in Nîmes (1984-1993), the Hong Kong International Airport (1992-1998), and the Apple Park in Cupertino, United States (2009-2017). To confront the work of architect Norman Foster is to immediately evoke the projects that appear most striking, those that blend in with the image of a city, a territory, or that simply have changed the shape of a site or the configuration of a place or square. With several hundred projects studied or realized on a global scale, Norman Foster has invested in the complexity of large industrial organizations.

As an architect of networks, exchange systems, transport, and communication organs, Foster has always sought to put the concept of environmental control at the heart of his creations.

As an architect of networks, exchange systems, transport, and communication organs, Foster has always sought to put the concept of environmental control at the heart of his creations. He developed a global systemic understanding of nature and technology, reconciling technological progress with a sustainable ecological approach. The notion of a system, central to all his work, stems from a comprehensive understanding of the environment, the biosphere, and the technosphere. For him, architecture must take into account the new modes of interrelationships between populations, nature, and technological environments.

Born in 1935 in Manchester, Foster graduated in architecture and urban planning from the University of Manchester in 1961, then obtained a scholarship to Yale University, where he earned a Master's degree in architecture (1961-1962). It was there that he met his fellow countryman Richard Rogers, future collaborator of Renzo Piano for the design and construction of the Centre Pompidou. In 1963, he co-founded the collaborative agency Team 4 in London with Richard Rogers and their then wives Su Rogers and Wendy Foster. In 1967, he founded his own agency, Foster + Partners.

The retrospective exhibition at the Centre Pompidou dedicated to Norman Foster traces the different periods of the architect's work over nearly 2,200 square meters, highlighting his significant achievements. Drawings, sketches, original models and dioramas, as well as numerous videos, reveal 130 major projects. Welcoming visitors at the entrance of the exhibition path, a large drawing cabinet displays notebooks, sketches, and photographs taken by the architect, never before shown in France. Because they are sources of inspiration for Norman Foster and resonate with his architecture, works by Fernand Léger, Constantin Brancusi, Umberto Boccioni, and Ai Weiwei, as well as industrial designs (like a plane and several automobiles) are also presented in the exhibition.

Frédéric Migayrou — You have often been associated with the high-tech movement. It’s an idea that you have dismissed, stating your preference for a more structural vision, in which architecture corresponds to the more measured ‘skin and bones’ principle evoked by Mies van der Rohe. The technology must be adapted and eventually, through its efficiency, gradually fade away, in keeping with the idea of ‘ephemeralisation’ put forward by Buckminster Fuller. How would you define your conception of technology ?

Norman Foster — I think that technology is a means to social ends – to lift the spirits and protect you from the elements. In other words, not just to be comfortable but to create a lifestyle – something which is about delight. What you’re describing as ephemeralisation is a means to that end. It’s really dissolving the structure and the services, integrating them so that they visually evaporate. If you look at the Centre Pompidou by Richard Rogers and Renzo Piano, it makes a celebration of its services and structural elements, both of which you can see on the outside. If you look at our Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, from the same period, you have a structure and all the services integrated into it. So, the structure is designed for the environmental performance, as well as the structural performance. The aim was to create a building which is healthy and breathing. I would say it is a personal approach, born out of the systems theory which was applied in other spheres at that time. Although my approach has evolved, the idea of ephemeralisation remains a constant to this day.

You’re a pilot, and you say you’ve flown something like seventy-five different types of aircraft. But you are first and foremost a glider pilot, which requires a very specific skillset. Often, you say that this role could be a metaphor for that of the architect. So what is your understanding of the role of the architect ?

Norman Foster — For me, there is sheer delight in the challenge of flight and a kind of magic every time I see an aircraft take off. There is the simple pleasure in defeating gravity, but if we take the aircraft, glider or helicopter as a metaphor for architecture, then it’s the ultimate fusion of the machine and nature. Those invisible upcurrents are enabling the glider to spiral and climb and then go to the next column of rising air, like a bird. So, it’s about reading the weather visually, and if you change one element, it affects the other.

If I pilot a helicopter, I’m probably holding the lever in my left hand. I’ve got my right hand on a control stick and my feet on the rudders. If I change one of these things, it affects all the others – like when I am designing a building. For example, if I change the outer skin of a building and let more light in, that has implications on all kinds of factors within. That systems approach is comparable to the control inputs on an aircraft. It’s about being sensitive to those shifts and the interactions between the different elements.

It is also the role and function of the architect that must evolve. Architects cannot simply be designers and creators, but must also coordinate multiple disciplines – a way of governing, of directing – which for architecture means piloting a project.

Norman Foster — I would counter-argue that this approach makes you more powerful as a designer – you are more integral to the entire process of design. So, it’s not the opposite of creativity; rather, it’s a means to being more creative and efficient, which in today’s terms means more sustainable. You may be able to steer a project towards using less energy and creating a lower carbon footprint. It’s more in harmony with the natural world, which, in a period of global warming, is the ultimate quest.

Artistic creation has a fundamental significance for you, one that you often relate to technology. You are a collector, and you have also commissioned work from many international artists. Artworks are integrated into many of your architectural projects. You have curated major exhibitions in Nîmes and Bilbao, in both of which art has been given a central position. Could you explain the role that art plays in your work?

Norman Foster — Over the decades, I have sought to bring the work of artists into the architecture of our buildings. It started in our first studio in the 1960s, where the first impression for visitors was a bold painting by a young artist friend, Marc Vaux, whose work we enjoyed and collected. Over time, the works of artists have become more integrated into our architecture; they have participated in the process of design, and the end result is richer for that more intimate involvement. In many cases, it has encouraged the artists to stretch their own boundaries of creativity. Examples abound.

In 1996, I approached Bridget Riley to contribute to Citibank’s headquarters in London. Before this, all of her work had been oil on canvas – vibrant patterns of colour, preceded by her pioneering op art in black and white. For the first time, she saw this as an opportunity for sculpture – a radical work that stretches sixteen storeys high in the staircase atrium, and that totally transforms the experience of circulating through the tower.

Many of our collaborations with artists started as family projects and then extended into professional assignments – occasionally it was the other way around. I had personally known Richard Long since the 1980s, and he subsequently contributed to two of our past homes. In both cases, his hand-applied imprints on mud had a profound and uplifting effect on the interior spaces. He went on to develop the same concept for the base of the Hearst Tower in Manhattan but at a civic scale. It is difficult now to imagine any of these locations without their works of art – they are central to the sense of place.

The same is true of the Reichstag, where I worked with five selected artists in their studios to ensure the maximum synergy between their chosen materials and the assigned spaces. The exchanges with these artists during visits to their studios, when we used scale models of the spaces, in some cases changed the direction of their art. Gerhard Richter wanted to do a work in coloured glass when he realised that we could provide him with the necessary technical expertise. Sigmar Polke was unsure about using the medium of electronic advertising until we encouraged him to do so. Günther Uecker was able with our help to design his first architectural space – the chapel of the Reichstag.

In 2018, on the twenty-fifth anniversary of the opening of our Carré d’Art in Nîmes, with its sequence of art galleries, I was asked by the city to curate a commemorative show to mark the occasion. For an architect, that was an ultimate opportunity to fuse the arts of architecture, sculpture and painting. It certainly set the stage for the more recent exhibition Motion – Autos, Art, Architecture at Guggenheim Bilbao that you mentioned.

From the time of the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation Headquarters, which at first sight appeared to be a high-tech building, you have consistently emphasised the importance of historical context, of a relationship to history. History is an active element in projects such as the British Museum’s Great Court and the Hearst Tower, both of which involve historic buildings. In contrast to the postmodern vision, it is important to you that such historical elements play a determining role, are ‘enacted’, in your projects. What exactly is your approach to history?

Norman Foster — You’re referring there to a theory proposed by R.G. Collingwood – it’s interesting that, as well as being a respected philosopher, he was also a practising historian and archaeologist. He saw history as the embodiment of emotion, having a subjective aspect as well as an objective, factual embodiment, rather like the art that I described.

It may be viewed as a cliché, but I have often said that if you want to know what the future will be like, then first you must look far back. You can see that approach through the imprint of history in projects like the British Museum. If you go back in time, you find that the heart of the original building was a courtyard, in between an original central library and the inner facades of the building, and this had been filled in over time. When we began our work, we felt there was an imperative to take away the accretions and to reveal the courtyard from the past.

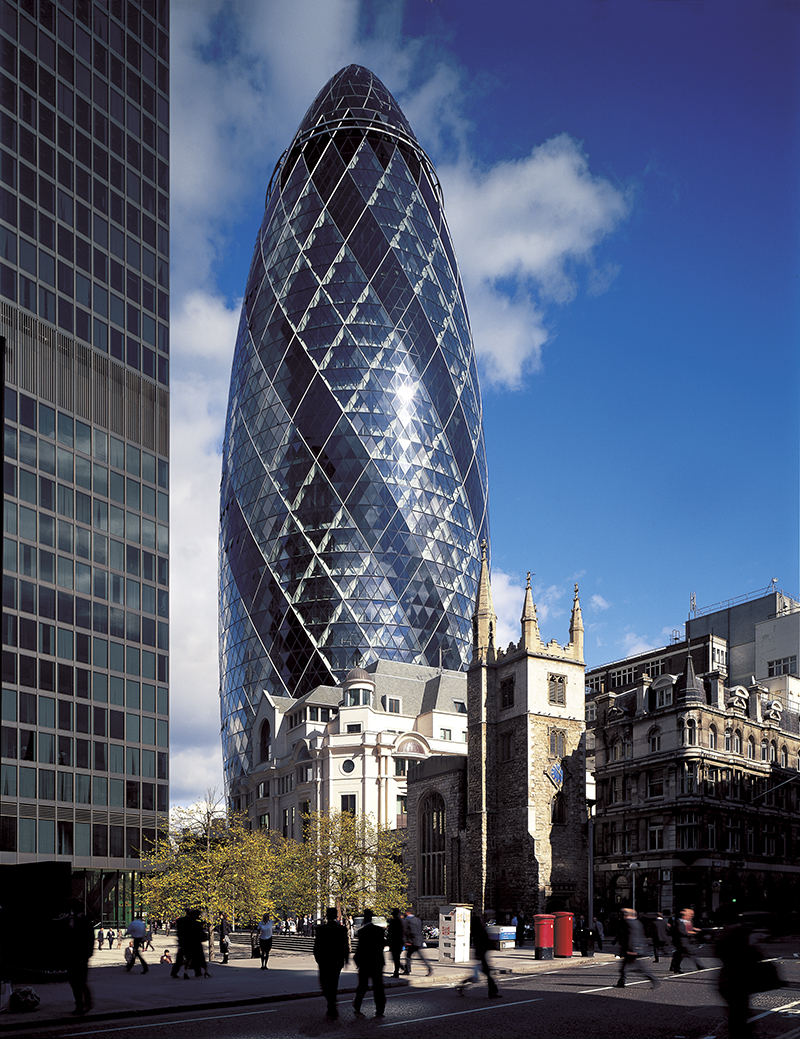

Another example might be Bloomberg’s headquarters, which is right in the heart of the City of London. The site was originally bisected by Watling Street, an ancient Roman road. We saw the project as an opportunity to reinstate the road, to take it through the buildings and create an arcade. Now, when you look at that arcade, you don’t think of a Roman road, but if you do the equivalent of an archaeological dig, then of course it’s there. So, I think that there is a very real element of learning from history and incorporating it into the present.

The notion of environment is central to your work. As early as 1971, with your Climatroffice project with Buckminster Fuller, and then in 1975, with your plan for the island of Gomera in the Canaries, you were developing the idea of the global, systemic management of environments. Across your projects, you have evolved multiple solutions to make construction sustainable, anticipating a number of later proposals that hybridise technologies and nature to deliver a healthy ecology. What is your vision for a sustainable future?

Norman Foster — Gomera was about touching the ground lightly, recycling waste as fertiliser, recovering water, creating breathing buildings and working with nature. All those ideas have since become fashionable, and more importantly, lifelines of sustainability. They were there during the very earliest days of the practice. For instance, the Climatroffice project imagined office decks within nature and trees; the trees would contribute to the air quality and absorb carbon dioxide. That project anticipated a number of things which entered the global consciousness later on.

It may be viewed as a cliché, but I have often said that if you want to know what the future will be like, then first you must look far back.

Norman Foster

A decade later, you had E.O. Wilson’s book Biophilia, which drew attention to the importance of moving from our mechanised world towards nature. All the manifestations that you refer to in those early days – which reflected passionately held beliefs about the importance of a view, top light and natural light – those have subsequently been proved to have validity, particularly by the Harvard School of Public Health’s studies.

But if we take into consideration another of your more recent projects, and one which could be seen as controversial – a nuclear microreactor – what is your vision of what could or should be the future of energy production?

Norman Foster — To go back to an earlier question, its future can mirror that of telecommunications, which has ephemeralised, eliminating the infrastructure of wires across the landscape, and the telephone exchange, with hundreds of people manually moving little plugs here and there. It has become something which fits into our pockets yet does communication on a grand scale.

We have seen the effects of a crumbling infrastructure of power distribution in California this summer, leaving two and a half million people scrambling for diesel generators. There has been a lot of research work done on nuclear energy, where you can have a microreactor that fits into a 6-metre [20-foot] trailer powering an entire Manhattan block. It is absolutely safe in terms of its fuel, has a maintenance-free life, and could power a small town autonomously – it is just one more example of possible ephemeralisation.

Societies that have a high consumption of energy also have lower infant mortality, longer life expectancy, higher quality of life, more sexual and political freedom, and fewer children, thus helping to stabilise the planet. So, there is a real imperative to open that access to energy to everyone on the planet, especially the 14 per cent of the global population who don’t have access to electricity, modern sanitation or clean water.

This brings me to a question about your conception of community, to borrow a notion from Serge Chermayeff. The idea of public space, of common space, is a preoccupation that runs through all your works. What is your vision of the morphology of public space?

Norman Foster — The infrastructure of public spaces is really the glue that binds individual buildings together. It determines the DNA of a city and the separate identities of, say, New York, Marseille or London. If we take Trafalgar Square as an example, closing one side transformed not just that space, but the whole quarter of the city. You can quantify the benefits: there are fewer accidents, it’s safer, the quality of the air is better and it’s quieter. Computer modelling by the design consultancy Space Syntax simulated the movements of pedestrians and we explored those results before any decision was taken. It’s essentially a bottom-up process and that’s why it’s quite time-consuming – because many people have to be consulted. But in the end, there is a consensus.

There is a real imperative to open that access to energy to everyone on the planet, especially the 14 % of the global population who don’t have access to electricity, modern sanitation or clean water.

Norman Foster

We’ve talked about the notion of place – the specificity of sites and contexts – a notion that seems to contradict another fundamental concept in all your work, that of mobility. As an architect of major international airports, of many transportation systems, of urban structures, but also of communication centres, networks have a central place in your approach to architecture and urbanism. How do you articulate this tension between place – the local – and your extensive understanding of mobility?

Norman Foster — I think there are those networks which are physical and there are the invisible networks in the sky, but at some point, they all come down to the physicality of a built element. In this digital world, with these invisible networks that connect us, it’s hugely tempting to go into an architecture which is a digital experience, and to rely on wayfinding by numerals, by letters of the alphabet, and so on. But I see it as a challenge to make architecture an analogue experience in a digital age. So, whether it’s an airport, a subway or metro system, somehow the architecture should guide you effortlessly. You shouldn’t have to stop and consult a map. In the same way, when an invisible network comes down to the ground, as at the Collserola telecommunications tower in Barcelona, there is an opportunity to celebrate it in the landscape. In that instance, it really touches the ground ever so lightly – it is a tensile structure that disappears against the sky. It is a celebration.

Through your interventions all around the world, through your experience of flying between sky and earth, and through your closeness to Buckminster Fuller, you have formalised a global vision of our ways, as humans, of inhabiting the Earth. The publication of the first full-disc colour photograph of the Earth in 1967 by NASA, which appeared on the cover of Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog the following year, reinforced our awareness of ecology, our consideration of the biosphere – of Gaia, to use a term popularised by Lynn Margulis and James Lovelock, and recently taken up by Bruno Latour. As an architect who has developed habitat projects on the Moon and on Mars, what is your vision of the Earth, of the future of humanity on Earth ?

Norman Foster — I’d like to think it was following in the footsteps of those revered individuals who have enabled us to see the world as an ecosystem. In microcosm, buildings are related to natural ecosystems, and my quest is for a holistic approach that achieves a balance with nature. Energy has to be at the very heart of that issue because it relates to every aspect of global warming and pollution. So, the quest for clean energy is not just about anticipating global population growth but also dealing with its implications.

To put that into perspective: in Africa, there are 600 million people without access to electricity and one-sixth of those people are in Nigeria. By its own estimate, in thirty years’ time Nigeria will need to consume fifteen times the amount of energy it does today, both to meet the needs of a growing population and to industrialise. So, if we look statistically at the form of energy that can occupy the smallest footprint on the planet, produce no pollution and have the absolute safest record – that is nuclear. It is the new generation of nuclear power, which has the promise of autonomy, that I find very exciting.

The hypothesis of a sustainable future often comes up in your remarks. How do you imagine it?

Norman Foster — My vision of a sustainable future is rooted in the clean generation of electrical energy, which is at the heart of combating global warming. Over a billion people at the moment live in informal settlements without, in some combination, access to electricity for heating and cooking, modern sanitation or clean water. Unless checked, it is forecast that by 2050 one in three people will suffer these conditions. So, we need an abundance of clean, safe and reliably sourced energy for a sustainable quality of life for all in future.

Like telecommunications in the past, before the age of the cell phone, we rely on massive, centralised power stations and endless transmission networks. With new-generation nuclear, we can industrialise miniature power plants. As mentioned earlier, a 6-metre [20-foot] standard container can house a sealed nuclear battery that, with a similar sized co-generator, can generate 10 megawatts, enough to power a small town or an entire Manhattan city block.

Incidentally, the statistics show that conventional nuclear plants are the safest way to generate electricity, and by a huge margin – even safer than solar. That is not to discourage the current transition to renewables – on the contrary we need all the weapons in the armoury, especially when the wind doesn’t blow and the sun doesn’t shine. We currently still generate 85 per cent of our electricity from fossil-fuel sources.

Given that we have the technology and means for a clean energy future, our cities will consequently be cleaner, safer, quieter and greener. Neighbourhoods will be more mixed and walkable; large-scale tree planting will create desirable microclimates and greater biodiversity; less space will be needed for mobility; urban farming will deliver fresher and better produce within the city. The global population will be stabilised, because those societies that currently have access to large amounts of energy for the most part require fewer dependents and live safer, healthier and longer lives. ◼

* Interview conducted by Frédéric Migayrou, curator of the exhibition, an excerpt from the exhibition catalog, Norman Foster.

Related articles

In the calendar

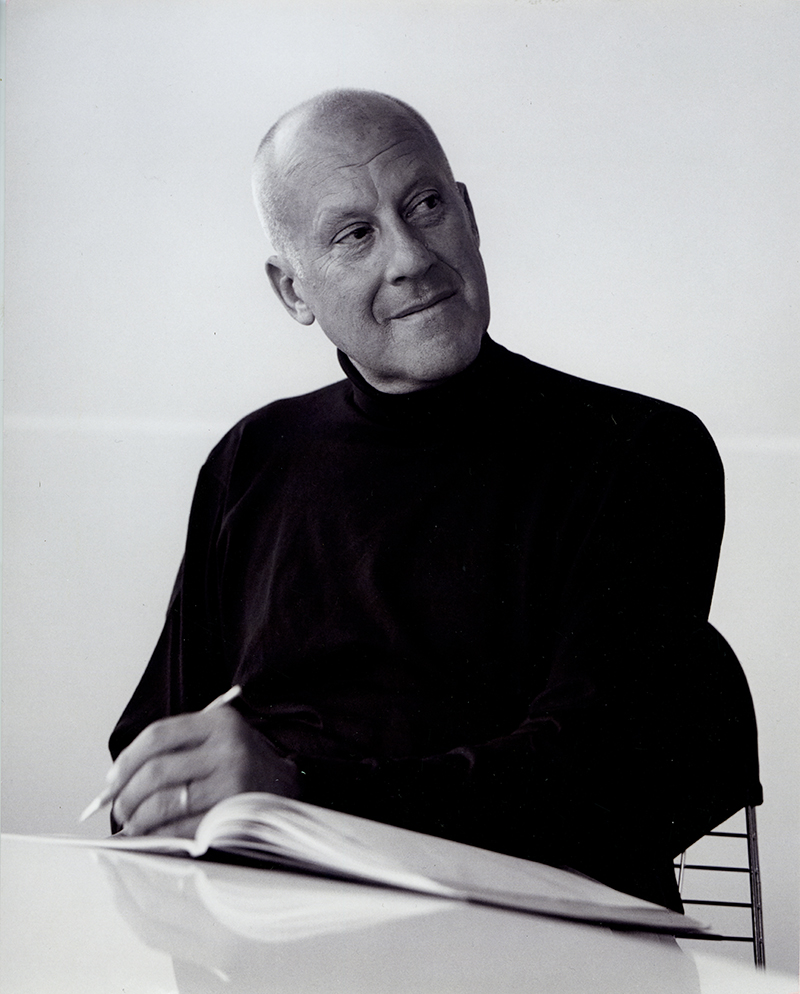

Portrait of architect Norman Foster

Photo © Yukio Futagawa